ARE WE AT WAR?

‘Conservation is war’ is a sentiment we often hear these days – and perhaps many readers will agree. But is it a war, or is it wishful thinking on behalf of those who want a decisive end to poaching? And if it is a war, do we really know who the enemy is?

Conflicts between conservation authorities and poachers are sporadic. The term ‘war’ might be better applied to the conflict between animals and poachers, where animal deaths run into the hundreds-of-thousands each year. But animals can’t fight back, so it is probably best described as genocide. As with human genocides in recent history, military intervention by governments has eventually put a stop to the slaughter; but it seems human sentiment does not extend to animals – they are not on the priority list of governments.

In spite of this, the efforts of various conservation authorities to protect animals throughout Africa are awe-inspiring. While vastly outnumbered, poorly equipped and poorly paid, they take incredible risks and are effective in preventing poaching to some degree, sometimes apprehending or killing perpetrators. But where there are successes in a few arenas, animals are still being wiped out in many others.

The regions under the greatest duress are those where poachers are well-armed and organised militia, such as in the DRC, or where poachers find little opposition, such as in Southern Tanzania. In the case of the DRC, the militia are not only supplemented by the profits from poaching, but also from illicit mining. Due to a devastating civil war and an armed scramble for resources, conservation authorities in this region have little to no support from the government, whose armed forces are split across many fronts tackling multiple factions. Conversely Tanzania faces no military intervention, yet Selous Game Reserve is steadily being cleaned out of elephants as poachers on cross-border raids from Mozambique find little to no opposition.

Even in South Africa – the African country best able to support conservation authorities with military training, equipment and funding – the tide is against them. Year-on-year the number of rhinos poached for horn goes well above a thousand, the chief perpetrators being poorly armed poachers crossing from Mozambique into Kruger National Park. The South African government does not appear motivated to preserve wildlife, as illustrated by a recent move to permit domestic trade in rhino horn – a dubious decision given South Africa’s enormous stockpile of rhino horn.

One country’s government does seem determined to protect its wildlife, employing the defence force in anti-poaching roles; but where Botswana may be closed to poachers, many other avenues remain open. Elephant populations are being wiped out in neighbouring Angola and there are indications of an increase in poaching across the river in southwest Zambia.

What is clear is that military operations in support of conservation are not on the agenda of most African governments; therefore this is, technically at least, not a war.

But let’s say it were. As any military leader worth their rank will agree, in a war there are tactics to apply beyond tackling ground forces. In his 500 BC ‘Art of War’ treatise, Sun Tzu wrote, “Foreknowledge cannot be gotten from ghosts and spirits, cannot be had by analogy, cannot be found out by calculation. It must be obtained from people, people who know the conditions of the enemy.”

Applying this to a conservation war would suggest that it is advantageous to understand the enemy – and that would mean accepting that the people carrying the poaching weapons are merely pawns. There are much more influential figures at play, namely traffickers, traders and consumers of animal parts who are the unwitting victims of ancient myths and modern propaganda perpetuating the sale of rhino horn, ivory, pangolin scales, shark fin and more.

People often rejoice when they hear that a poacher has been apprehended or killed, but unfortunately poverty is the circumstance that many poachers find themselves in. Since poverty and hunger are more compelling than any military doctrine, marginalised people such as these can be easily exploited to kill animals for profit.

The number of desperate people on the margins of wildlife areas is legion, which opens up a fundamental issue: while the public’s energy is focused on rallying against poachers, we deny them their humanity and forfeit our own. We forget our governments’ responsibility to tackle poverty and we ignore the possibility that lifting marginalised people out of poverty will not only help them to live a better life, but will also prevent the poaching of wildlife – if not for profit, then for food.

To tackle the real enemy we need to motivate governments – not only for military support, but also for much stronger intelligence and law enforcement focused on apprehending the recruiters, traffickers and traders. In tandem with this, we need a focus on educating consumers about the futility of using animal parts for medicine and the global consequences of their actions. Governments need to support marginalised African communities so that they do not fall prey to criminal poaching networks; meanwhile, we need to educate the global animal-loving public that their energy and funding should be put into motivating governments to conserve wildlife, not into small operations that have no positive influence on conservation.

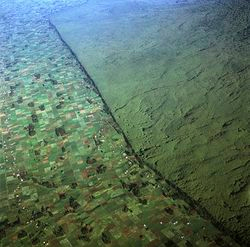

We should realise that our planet’s wilderness has been decimated for own pleasure and sustenance. Entire ecosystems have been eradicated to make way for agriculture. We have hunted thousands of species into extinction. That we allow it to continue within the few scant wilderness areas that are left is an abomination.

If conservation is war, then it is not a war on poachers: it is a war on greed. As the Roman philosopher Seneca said, “For greed, all nature is too little.”

Take part in debates like this and many others at the 2018 edition of the Conservation Lab, where the leaders in conservation, travel, technology, behavioural sciences, philanthropy and government will gather under optimal conditions for creative thinking and collaborative innovation, with the aim of igniting conservation efforts. To get involved, contact paul@beyondluxury.com.